Why We Don’t Tell People About Our Dreams

I am always honored – and humbled by the dreams clients have shared with me over the years, in my role as a psychotherapist.

They often told me more than I asked. Stories and context and layers came out. I learned about self-harm, trauma, phobias, child abuse, rape, sexual assault, erectile dysfunction, suicide attempts, and more. Always followed by this statement: I haven’t even told my family this. No one knows.

What I came to understand from this was that it was easier to tell things to strangers (although, paradoxically, as our work went deeper, the therapeutic relationships became stronger, despite maintaining the emotional distance and objectivity needed to get the work done).

This same pattern can be found in discussions about dreams. This struck me as odd seeing as suicide, erectile dysfunction, and sexual assault carry an immense social and societal stigmas, whereas dreams arguably do not.

And yet, despite that, dreams do carry a stigma of shame. Sharing our dreams carries shame. Shame about the content of the dream. Shame about possessing the dream. Shame about our inability to fulfill, begin, or finish the dream.

Could it be that the fear of mockery, dismissal, judgment, minimization, and rejection is what keeps people silent?

I did not expect so much secrecy. The unspoken message regarding dreams seems to be; “We carry our dreams in secret. Hold them tight to our chest. And tell no one.”

However, once you tell someone, then there’s a Real No Kidding expectation for you to do something about it.

Because if you see that person again, they will ask you, “How’s the book going?” and you will have to say, “I haven’t worked on it at all since I last saw you.”

I wondered why full-grown adults in their 30s, 40s, 50s, and 60s felt comfortable telling me their secrets back in the psych clinic. I thought maybe it was because I was exceptionally great at my job and had nailed the affect and dispositional aspect of securing trust with participants.

It had nothing to do with me and everything to do with shame and accountability. If you’re never going to see me again, you don’t risk being asked, “How are you? Are you still cutting yourself? Still throwing up your food?”

With a stranger, you can release the tension of your secret without any accountability.

You aren’t on the hook. You don’t have to do anything about it. We are terrified of making our dreams come true.

Quitting your job and moving to Bali is not what I’m talking about. That’s not a dream, that’s the plot of Eat Pray Love. And that wasn’t a dream either, that was a healing journey. Her dream was to be a writer and to be free from social convention and an oppressive marriage.

Doing requires defining and defining requires telling because none of this is possible in isolation. It happens in community with others who support you and keep you on the hook – not with shame, but with encouragement + recognition. Recognition that this isn’t linear, there are many paths forward, and most of the time you’ll get it wrong before you get it right. That recognition only happens in connection with those who are willing to lean into the vulnerability of their own dreams.

Why You Shouldn’t Tell People about Your Dreams

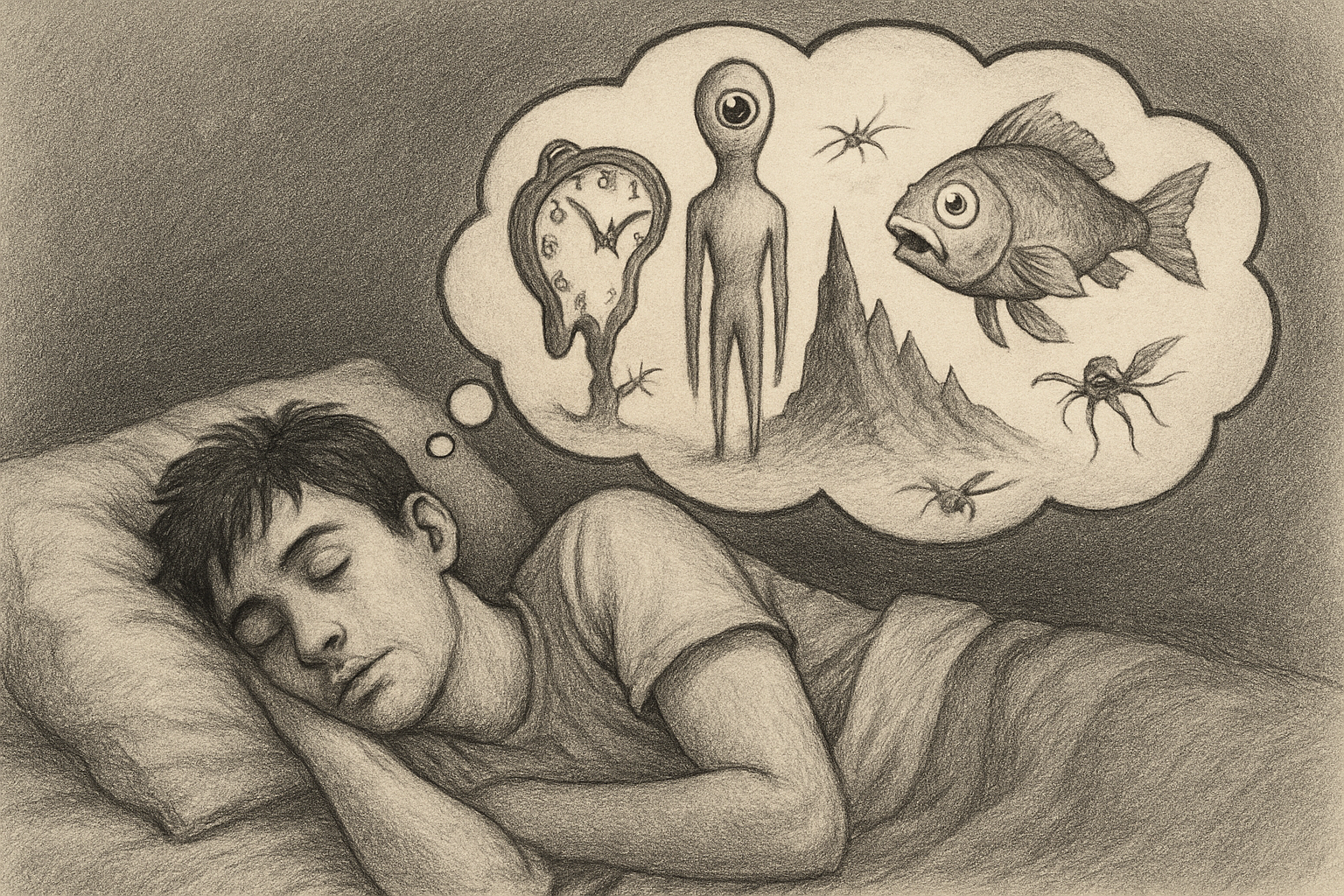

There are several major theories about why we dream. One is the activation-synthesis theory, which holds that dreams are interpretations by our forebrain of essentially random activity from the spinal cord and cerebellum during sleep, especially rapid eye movement (REM) sleep.

Part of the explanation for why dreams can be so weird is that they are interpreted from chaotic information. The evolutionarily older parts of our brain are also the seat of our basic emotions. According to this theory, the emotion comes first, and dreams are made to make sense of that emotion. Evidence for this position comes from scene changes that happen: when we have anxiety dreams, for example, they often switch from one anxious situation to a different one—so rather than us feeling anxious because of the content of our dream, it could be that our feeling is causing an anxious narrative in the dream!

Another major theory of dreaming is threat-simulation theory, which holds that the evolutionary function of dreaming is for us to practice how to behave in threatening situations. There is a lot of evidence for this theory, too.

First, most dream emotion is negative. Also, people tend to dream of ancestral threats: falling, being chased, natural disasters, and so on. These frightening elements are overrepresented in dreams—that is, we see them in dreams much more than our experience in our day-to-day world would predict. Many people dream of being chased by animals, but how often does this actually happen to people? The overrepresentation of animals chasing us in dreams, especially for children, suggests that we have some innate fear of them. In contrast, we do not dream of modern threats, such as heart attacks, as much as we would expect if dreams were based on the problems we actually face in today’s world.

These two theories of dreaming are often presented as competing, but as far as I can tell, they are compatible—that is, even if dreams are interpretations of chaotic input from the spinal cord, there is still a theory needed to describe how that chaotic input is elaborated into narratives that we experience as dreams, and it is quite possible that the mind takes advantage of this opportunity to practice dealing with dangerous things.

Why do we feel the urge to talk about our dreams? Perhaps we like to talk about dreams to help us prepare for how to act in dangerous situations in the future.

Which leads us to why we find our own dreams so interesting. There are three reasons, based on known psychological effects, although all are speculative, in terms of my application of them to dreams.

The first is negativity bias, which makes us pay attention to dangerous things. Because most dreams are negative (support for the threat-simulation theory), our bias in favor of negative information makes them feel important.

The second reason has to do with the emotional primacy of dreaming—because so many dreams are so emotional, they feel important in a way that people hearing about them, not feeling that emotion, might find hard to relate to.

We tend to think of dreams as being really weird, but in truth, about 80 percent of dreams depict ordinary situations. We’re just more likely to remember and talk about the strange ones. Information we do not understand can often rouse our curiosity, particularly in the presence of strong emotion. Just like someone having a psychotic experience, the emotional pull of dreams makes even the strangest incongruities seem meaningful and worthy of discussion and interpretation.

These reasons are why most of your dreams are going to seem pretty boring to most people. Nevertheless, if you’re going to talk about your dreams, choose the ones in which you deal with a problem in some new way. The negativity bias would make them more interesting and if you feel that you learned something new about how to deal with a threat (real or perceived), maybe your audience will, too.

Modern Lives = Less Attention to Dreams

I believe people in the West largely ceded their sovereignty over dreams in the late 19th century, particularly due to rising industrialization, along with the emerging disciplines of neurology and psychology. In line with the spread of secularism and a growing intolerance for so-called “popular superstitions”, dreams as external messages no longer made sense by the mid-20th Century.

But not everywhere – a few years ago I gave an online talk to an women’s empowerment group in Hong Kong and I’ve never given a talk before or since before such an enthusiastic audience. They asked questions, shared details and asked me – and even their fellow attendees what certain things meant!

I don’t think anyone would mistake the Chinese people as being somehow backward or unsophisticated because they still listen to and openly discuss their dreams; in fact, in the ancient Yellow Emperor’s Classic of Medicine, written between 4-2 BCE, dreams form a part of diagnosis and are used as such up until the present day. This is also true of the healing tradition of Ayurveda from India, an even older comprehensive healing system developed between 2500-500 BC.

I have also found similar attitudes towards dreams across Africa, among Native Americans and Australian aboriginal people. It would appear that older cultures with longer memories have retained this relationship with dreams, while modern Westerners did not, as they sought to release the past in a drive toward modernity.

Sigmund Freud, I believe, paradoxically made the flight from dreams even greater – having labelled dreams as by-products of our repressed desires – lusting after people, places and things – that the baby ended up being thrown out with the bathwater, so to speak!

The omnipresence of the Freudian model of dreams as repressed wish-fulfilments – which looked to the past of the individual, and not the future – played a key role in making people think that dreams were internal, private matters, and not the kind of thing you discussed with others.

People still have dreams that they consider to be prophetic, but it was no longer considered appropriate to share them with public authorities because the dream vernacular was no longer spoken at large.

Another reason why people don’t talk about dreams so much any more relates to humans having turned night into day and ignoring natural waking and sleeping patterns.

As our 9 to 5 and 24/7/365 lifestyles developed in the 20th Century, nocturnal environments became almost permanently illuminated by artificial light, both indoors and out.

Work patterns suddenly changed as night-shifts became an essential component of modernity after WWII and this has had dramatic effects on our biological clocks, as well as those of the animals and insects around us.

Post-WW II economic transformation led to an astonishing loss of the night sky through light pollution, just as it has led to the loss of a whole range of social customs associated with the dark, especially storytelling. We now rely on radio, television, and movies to tell us stories at night.

However, despite our modern gadgets, our ancient reptilian brain continues to dream, practically from the time of conception until we die. Although we may not have time to remember dreams, our bodies will always make time to dream.

People share all kinds of personal information at the watercooler these days and mindfulness is all the rage -so why continue to ignore such an important life experience?

Catch up with me live as I look further into this subject on February 3rd!

Links to the live are below:

Leave a Reply